Is Anyone Else Alarmed by the Decline of Civility?

Civility is disappearing. Public meetings turn into shouting matches. Social media feeds overflow with personal attacks. Customers berate service workers. Even in workplaces, people talk past each other instead of to each other.

And it’s not just about rudeness. It’s how quickly conversations escalate, how little space there is for listening, and how disagreement turns into hostility. Civility isn’t about being well-behaved or avoiding conflict. It’s about how we engage—even when challenging norms or shaking things up.

Real change has never come from people simply being “nice.” It has come from people speaking up and staying in relationship with one another. Civility allows us to break barriers without breaking connections.

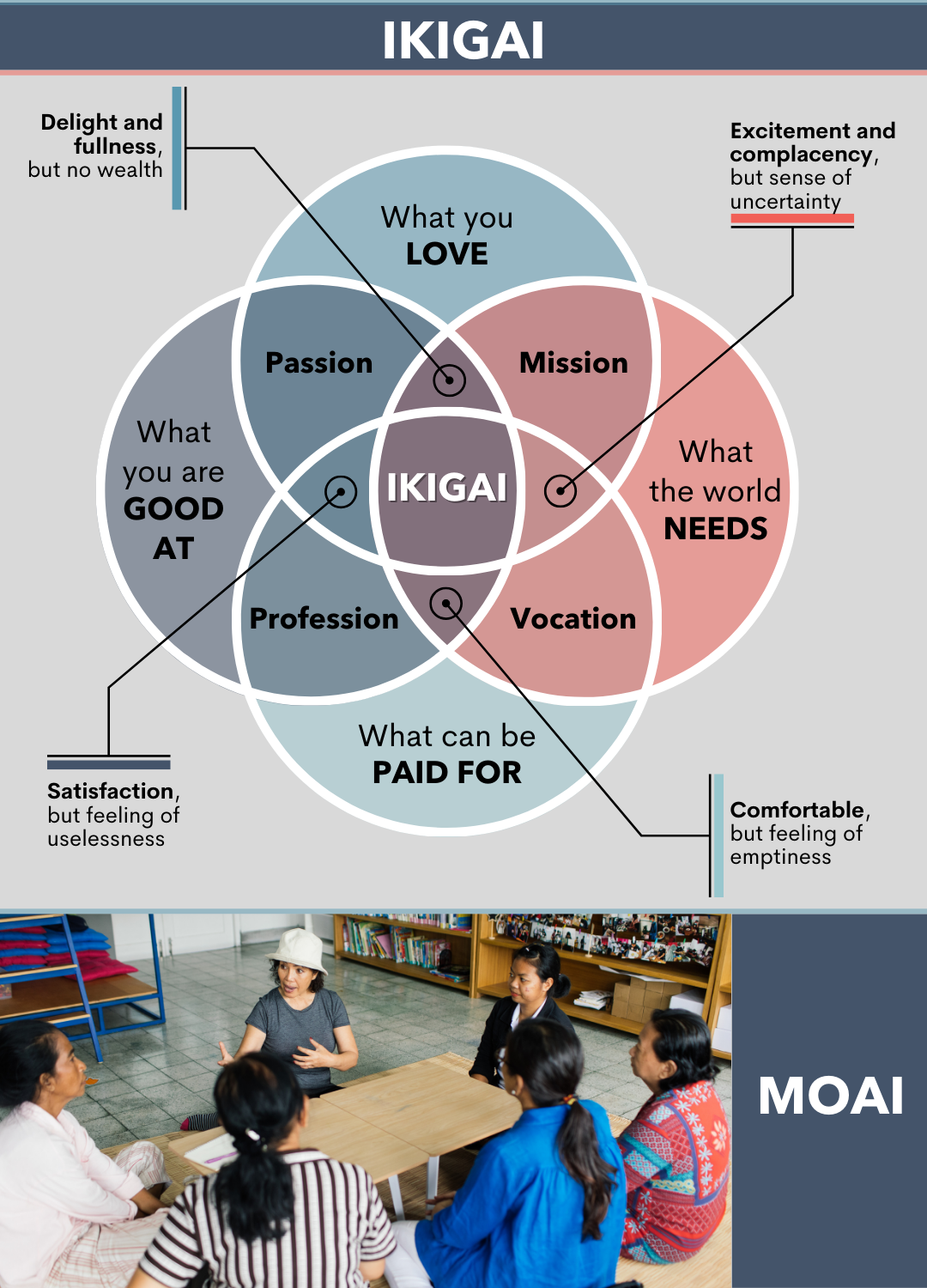

Civility Creates Community and Strengthens Peer Networks

When incivility takes over, people disengage, avoid tough conversations, or retreat into echo chambers. Over time, this fuels loneliness and isolation.

On the other hand, civility builds strong teams, workplaces, and neighborhoods. It makes people feel heard, valued, and more willing to participate.

Peer networks—professional, academic, or social—depend on civility. A thriving workplace or grassroots movement requires an atmosphere where people feel safe to share ideas. Civility paves the way for individuals to connect and form a true community.

Civility and Diplomacy: Learning From One Another

Civility and diplomacy go hand in hand. Diplomacy isn’t just for world leaders—it’s a skill we all use in daily life. Whether negotiating at work, leading diverse teams, or collaborating across cultures, diplomacy requires listening, thoughtful communication, and relationship-building—all hallmarks of civility.

Diplomacy isn’t about avoiding conflict; it’s about navigating it productively. The best diplomats don’t just argue their points—they learn from others. Civility enables that kind of meaningful dialogue.

When civility is abandoned—whether in politics, business, or everyday interactions—trust erodes, relationships break down, and opportunities for cooperation are lost.

Where Civility Has Gone Off the Rails

We see examples of incivility daily:

- Breakdowns in Diplomacy: Dismissiveness and hostility in high-stakes negotiations weaken global cooperation and stall progress.

- Social Media’s Callout Culture: What was meant to connect us often turns into a space where a single misstep—sometimes even a misunderstood comment—leads to public backlash.

- Toxic Workplace Cultures: When people don’t feel respected, collaboration and innovation suffer, and disengagement rises.

Where Civility Has Made a Difference

Despite the challenges, civility still drives meaningful change. It is evident in processes like Open Space Technology (OST) and Restorative Justice (RJ), which create environments where people can engage in honest, respectful dialogue and tackle big issues through a shared sense of ownership and problem-solving. It also shows up in these contexts:

- Programs That Foster Dialogue Across Divides: Organizations like Tomorrow’s Women, which brings together young Israeli and Palestinian women, and The Sustained Dialogue Institute, which fosters conversations in divided communities, show that structured, civil dialogue can bridge deep divides.

- Cross-Industry Collaboration in Business: Successful multinational companies prioritize civility-driven negotiation, strengthening partnerships and decision-making.

- Diplomatic Success: The Colombia Peace Agreement – In 2016, the Colombian government and FARC rebels ended five decades of conflict through civil negotiations, trust-building, and diplomacy. Instead of relying on force, leaders engaged in dialogue, proving that even deep divisions can be healed through civility.

Civility Starts with Small Choices

We can draw on these successes and make a difference in our workplaces and our relationships.

Civility isn’t about avoiding hard conversations. It’s about ensuring they remain productive. And while large-scale change matters, the real shift starts at the micro level—in everyday conversations, workplaces, and interactions.

So before sending that dismissive email, interrupting a colleague, or shutting down a different perspective, let’s take a beat. A single moment of civility—a pause, a question, an act of listening—can change the tone of a conversation and create space for connection.

Civility isn’t about pretending we all agree—it’s about ensuring we don’t lose each other in the process.

Where have you seen civility make a difference in your workplace, team, or community?